Population Management

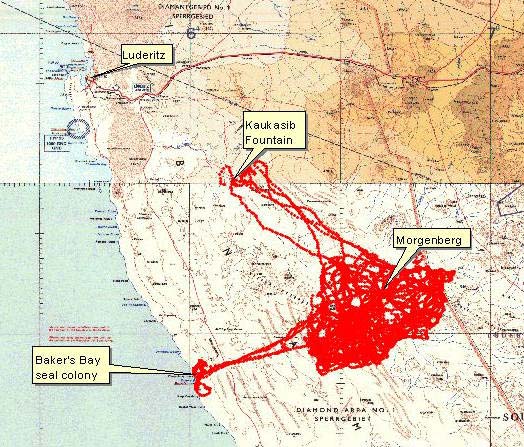

Radio Tracking Radio telemetry is a great way to monitor species populations, for it tracks an individual's movement, home range, and behavior. Radio collars are placed onto an animal such as a lion or rhinoceros, to send out a pre-set frequency signal that can then be detected by a receiver antenna. After a collar is put onto the tranquilized animal, the researchers can then track the animal by picking up the signal given off by its collar. GPS radio collars can also collect data that tells researchers about the animal's behavior. They can detect the animal's movement and so they identify when the animal is active and when it is at rest. (23) Radio telemetry is a great conservation method because it allows researchers to find the best way to protect a species based on its behaviors. |  |

|  |

| Camera Traps Motion-sensor camera traps provide a great way to monitor wildlife populations, for they can be placed in a preferred area and take pictures of any animals that wander through the range of view. The Wildlife Picture Index (WPI) stores these photos to assess population fluctuations. Statistical analysis can show which areas need more protection based on declines in biodiversity. (24) |

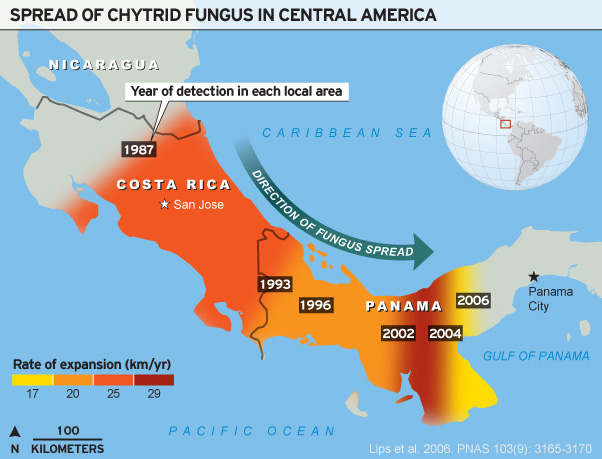

Disease: The Chytrid Crisis In some cases, the biggest threats to wildlife populations are pathogens. Diseases occur naturally, but they can be triggered by human activities. A great example of this is the Chytrid Fungus, which affects amphibians. Amphibians are biological indicators because of their permeable skin, in which they are the first ones affected by pollution, climate change, and pathogens like the Chytrid Fungus. (11) The Chytrid species, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, is unique in that it is the only type of Chytrid that grows on a vertebrate, which happens to be amphibians. The disease caused by the fungus is called Chytridiomycosis. When large amounts of the fungus infest the inner skin cells of the amphibian, it alters the structure of the outer skin layer, hardening the skin and decreasing permeability. Because amphibians drink water, absorb electrolytes, and sometimes even breath through their skin, the fungus causes cardiac arrest or suffocation. (25)

|  The Chytrid Fungus has played a big part in leading to the decline in global amphibian populations. However, not all amphibians are affected by the fungus; in fact, species like the American Bullfrog are resistant to it, but can introduce it to more sensitive species. The exact reason for this resistance is not known, but scientists speculate that symbiotic bacteria on the skin may discourage the fungus's growth. (25) Scientists are racing against the clock to study wild populations of endangered frogs, hoping to find ways to control the spreading disease. One way scientists have discovered to control the disease is to capture wild frogs and breed them with a gene that promotes immunity. The major histocompatibility (MHC) complex is a gene that promotes immunity to the disease, so breeding frogs with this gene can produce disease-resistant frogs that can be reintroduced back into the wild. (26) |

Conserving Evolution The Red Wolf, Canis rufus, has historically been considered a separate species from the Grey Wolf, Canis lupus. The Red Wolf used to be abundant in the eastern U.S, but now is critically endangered, and depends on captive breeding and reintroduction programs. However, some people speculate that the Red Wolf is not actually a separate species, but rather a hybrid between a coyote and a Grey Wolf. The hybridization would have been the product of human settlement in North America, shrinking the species' territories and causing populations to mix. Scientists have compared the two species' skull characteristics, mitochondrial DNA, and microsatellite DNA, and it appears that the Red Wolf is a distinct species that has only recently been replaced by coyote hybrids in most of its range. However, the hybridization hypothesis tested in the 1990s still proves plausible in that the red wolf hybridized before human settlement. |

The current cost of conserving and reintroducing Red Wolves into the wild is $4 million annually, so deciphering the genetic purity of the Red Wolf is crucial. It is the conservationists' job to conserve the process of natural evolution, so if the Red Wolf never hybridized before human disturbances, we must keep it that way. (27)  |

For more information about how to support wildlife conservation, visit:

Back to In-Situ Conservation | What is Ex-Situ Conservation? |